Plato

Ghassan Shahzad

If Socrates is the most influential philosopher in the Western tradition, then Plato (427 – 348 BC) ought to occupy the seat one rank lower, for it is by Plato that we know Socrates as we do. Furthermore, Plato — as shown in his later works — was a highly original philosopher of his own. He was also, like Socrates, a teacher — he even founded an academy, his Lyceum. From there came his influence upon Aristotle, the next great philosopher of Ancient Greece, and the man to complete the triad — Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. We know more of Plato then Socrates in a sense, but there are still debates over the authorship of the various works attributed to him and his thought.

Table of Contents

His Life

Plato was an aristocrat: birth name Aristocles, he was born to one of the most elite Athenian families. His lineage led all the way to Poseidon, the god of the sea. He was also a genius, and excelled in almost all matters. His nickname, ‘Plato’, was given to him for his physical prowess, the Greek word Platon meaning something like ‘broad’ or ‘wide’.

Plato was born to an Athens in turmoil. Constant (losing) warfare with the Spartans and rampant internal divisions were just two problems it faced. When the Athenians finally surrendered to the Spartans, who installed their infamous Thirty, Plato’s family was part of this Thirty. When the Thirty fell, the democrats tried and had Socrates executed.

These events left the greatest impact on Plato, and imbibed a hatred of democracy — and its constituent mob and demagogues — within him. Still, he held no compulsions towards the Thirty — and the Athenian elites more broadly — either. They were cruel, greedy, and self-centered. He channeled his disillusionment into his philosophy, as we will see.

Perhaps for fear of his own life, or out of this disillusionment, Plato went on a journey for twelve years before returning to Athens. He travelled perhaps all the way to the Ganges. He learned from all manners of culture and people: with Euclid himself, with the Pythagoreans; with the Egyptians, whose notion of priesthood no doubt inspired his view of the philosopher-class; and many others.

When he returned, he founded his Academy. He was forty at the time, and would spend the rest of his life attempting to cultivate philosophers in this Academy, that they may do their city some good. Like Socrates, Plato was not just an academic philosopher — he believed in acting upon, and passing on, his ideas, and for this end his Academy was the vessel. He lectured there until he died peacefully, at the age of eighty, at a pupil’s wedding.

His Thought

Plato was perhaps the first philosopher to weave together a philosophical ‘project’ — a grand, unified ‘vision’ for all ideas and topics philosophy deals with. Whereas his predecessors dealt with limited topics and some adjacent topics — the Pythagoreans with math, the pre-Socratics with metaphysics, and Socrates with ‘moralism’ — Plato touched on all topics de rigeur. Together, his views are known as Platonism.

Epistemology

The Context

And to begin developing such a project, one must start at epistemology — the study of knowledge. If we can’t even agree on what the ’truth’ is, then how will we make a compelling ethics or politics? The predecessor strands in this regard were that of the Sophists: sophistic skepticism and its resultant ethics of moral relativism; and those of the pre-Socratics.

Let us examine the latter, for their views were great influences on Plato: Parmenides and Heraclitus held two opposing views apropos the nature of reality. The former held that reality was static and constant, while the latter held that the ‘only constant is change’. These can be considered the main pre-Socratic currents. But Plato asked, ‘what if it was both’? This dualism held that there were two realities: one Parmenidean, and the other Heraclitean. The former was immutable, eternal, and static. The latter was our world of sensible reality, in constant change.

The Sensible World

There is obviously the sensible — Heraclitean — world. We experience it all the time. And yet, it can not be said that this sensible reality is a perfect representation of the nature of reality. That would mean only ‘appearance’ and no knowledge or certainty, especially since this world seemingly changes constantly. As Heraclitus said, ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river, and he’s not the same man’. How then are we to determine how rivers, generally, work, when the ones in our sensible world are clearly unreliable? Do we not bother, and abdicate our responsibility (as philosophers)? To Plato, such a world would be the world of the Sophists — a world, mind you, that he was diametrically opposed to.

The Theory of Forms

Therefore, Plato argued for a world — a Parmenidean world — of permanence. It exists independently of the Heraclitean reality our senses perceive, and we can have knowledge of it — as opposed to only opinions of the Heraclitean world. Within this world would be Forms (capital F). Of these, we certainly know that Forms are unknowable to the senses, and are the essences of all things they represent; they are not physical; they are also not part of any individual’s mind, and are thus not matters of custom. They exist on their plane of existence, a world that generally does not adhere to the same rules as ours. Plato himself, and though this Theory of Forms was the epistemological basis of most his thought, did not quite develop his theory. Thus, there is considerable controversy as to what exactly he meant by Forms.

The Allegory of the Cave

To illustrate the Theory of Forms, Plato uses his famous Allegory of the Cave. Imagine a group of people whom, from childhood, are bound to the walls of a cave. Their only source of light is far above them. These people only know of the outside world and its inhabitants from the shadows cast by that light. Of course, these shadows are unrepresentative, but the people don’t know that — for them, these shadows are reality.

These people are meant to represent us. We see only shadows, and we take them for the real thing — the Form. Outside the cave is the world of Forms, and philosophers who venture out into this world must do their duty, return into the cave, and bring as many others out as they can. But a man who left, and was exposed to the sunlight, would be blind upon his return to the cave — the prisoners would take this as a sign that leaving the cave leads to bad consequences, and may even harm the philosopher — as they did to Socrates.

The Divided Line

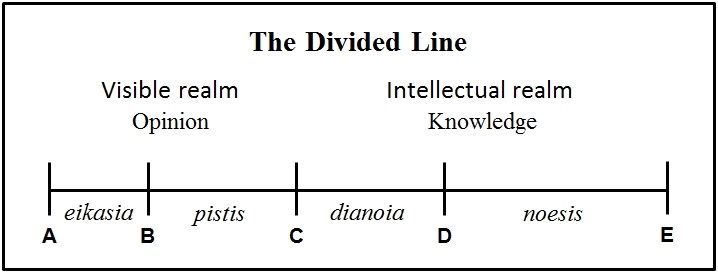

So far, Plato has split his epistemology in two: the sensible world and the mere opinions we can derive from it, and the world of the Forms and the true knowledge we can derive from it. He also calls these the realms of becoming and being, respectively; in the former, things are constantly changing (becoming), while in the later they are unchanging and absolute (being). But these categories can themselves further be split into two categories. Plato illustrates this entire ’layout’ using the idea of a divided line.

AC represents the realm of becoming, while CE represents the realm of being. AB is eikasia (delusion), the lowest state of living (that of the prisoners in the Allegory of the Cave), where you take everything your senses perceive as knowledge. BC is pistis (trust); it is a more lucid thinking than AB, but still suffers from flaws. CD is dianoia (ratiocination), where you can finally see images of Forms. Finally, there is DE, noesia (higher reason) where you can begin to comprehend the absolute Form of the Good; the Good can be seen as a ‘Form of Forms’, the greatest of all Forms.

Taking the example of a person: eikasia would involve knowing them through a photograph; pistis would involve knowing them personally; dianoia would involve knowing their form (i.e. Human); and noesia, as Plato describes it, is a sort of intuition that allows us to apprehend the highest levels of Forms.

From Here

Despite its flaws, from this idea of the Forms, and its proof of the existence of permanent knowledge, does the rest of Plato’s philosophy emanate. It is impossible for us to hold scientific knowledge of the particulars, given their ever-changing nature. Any inquiry into the condition of the world or the condition of man, therefore, must be focused on Forms. This will allow us to break free from the chains of Sophistic thinking.

Furthermore, Plato holds the view that ’the soul has [already] learned all things’. Essentially, we are all born with knowledge of the Forms (what he means by ‘all things’). To learn — really, rediscover — this is not impossible. We must simply be careful not to confuse the particular for the absolute, the opinion for actual knowledge.

You might see a pattern of elitism in Plato’s epistemology. In the Allegory of the Cave, for instance, there is the philosopher who ventures out; the blind masses within; and when the philosopher returns and tries to guide them into the light, they lash out. Perhaps the philosopher is meant to be Socrates. Regardless, this would inform Plato’s hierarchical (with the philosophers at the top, of course) and rigid society, as laid out in the Republic.

Ethics

It can certainly be said that Plato was the first of the philosophers to start focusing on political philosophy. His political philosophy was, of course, subordinate to his epistemology foremost. It was also subordinate, perhaps, to his experiences in life — especially the execution of Socrates, as discussed previously.

The Whole

For Plato, the question of such issues as ethics — which we are now equipped to handle — are impossible to tackle on an individual level. Ethics for instance, in Plato’s conception, governs how we interact with others (communities, states, etc.). Therefore, in advancing his conception of ethics, Plato uses abstraction — he deals with the state and society in whole.

Plato’s Conception of Justice

What governs the relations between the individual and society, or the state? According to Plato, ‘justice’. Plato uses the word justice to refer to morality in general. Therefore, a just person is a moral person, a just state is a moral state, and so on. We can use the terms interchangeably.

How do we judge, for instance, the justice of an action? For Plato, we see how it affects their community. The most just individuals are those that fulfill their responsibilities in the state and society — nothing more, and nothing less. This is called a functionalist theory of morality. This sort of morality gives way to Plato’s rigid hierarchy of state and society. To Plato, it can be said, every man is born for a purpose, his purpose almost invariably refers to his role in the state, and to be good is to fulfill this purpose perfectly.

The Needs

But what if the state is unjust? In such a case, the individual will not be able to live a just life, no? To determine whether a state is unjust or not, we need to look at the needs it fulfills of its constituents: their ’nourishing needs’ like food, shelter, water; their protection needs like defense, policing; and finally, their ordering needs. The state fails at these objectives for many reasons: one element of the state might encroach on the responsibilities of another, neglect their own, or whatever else. Regardless, the general issue is one of imbalance.

Plato’s Virtue Ethics

For Plato, virtue too is functionalist. A state is just if all its constituent parts fulfill their roles harmoniously; similarly, a man is virtuous if his soul performs its functions harmoniously. Specifically, there are three parts of the soul with different functions: reason, spirit, and appetite. He uses the analogy of a chariot with two horses: one horse is spirit, which yields to the merest whisper of the rider; the other horse is appetite, our natural desires, which are insolent and extremely hard to control. The rider is reason, and he must control both to achieve a good end.

The Cardinal Virtues

But where should reason lead the horse? Towards the four cardinal virtues: temperance (“nothing in excess”), courage (for the warrior-class), wisdom (for the philosopher-kings), and justice. You might say, Plato has finally broken from the rule of three. But really, the first three are the main virtues — justice is essentially the product of abiding by them.

Politics

Plato’s Republic is what we now call a ‘utopia’. An ideal form of a perfect government (in the eyes of Plato). To achieve his Republic is essentially impossible, but it is unlikely that Plato intended for us to read the Republic in that way. It can be seen as two things: an allegory; and an ideal. Contemplating an ideal is a useful thing even if we can’t achieve it. For instance, you know you will never be ‘perfect’. And yet, you ought to strive to be perfect regardless, even if it is impossible. Similarly, our states (in Plato’s view) should strive to emulate his Republic, even if they will never perfectly do so.

The Cycle of Government

For Plato, forms of government follow a sort of evolutionary cycle. The first form is oligarchy, the rule of the few. This form of government is notably materialistic, and eventually alienates the poor to the point that it is overthrown and turned into a democracy. A democracy’s main distinguishing feature is a lack of temperance, resulting in a constant state of change — it is stuck in the state of becoming.

The worst sin of democracy is its excessive love of liberty. This leads to a complete breakdown of Plato’s rigid social hierarchy, makes incapable the ruling class, and also breeds in its citizens a child-like sensitivity such that ’the least vestige of restraint is resented as intolerable, till finally, as you know, in their determination to have no master they disregard all laws, written or unwritten’.

This cycle ends in tyranny. Democracy proves a breeding ground for its sort of Last Man — one who indulges his every passion, considers himself master of all man and God. Every worst aspect of democracy — the lack of temperance in the drunkard, the prostitute, and banker — will culminate in this man. And he will make the democracy collapse under its own weight, leaving a tyranny.